Wallcharts

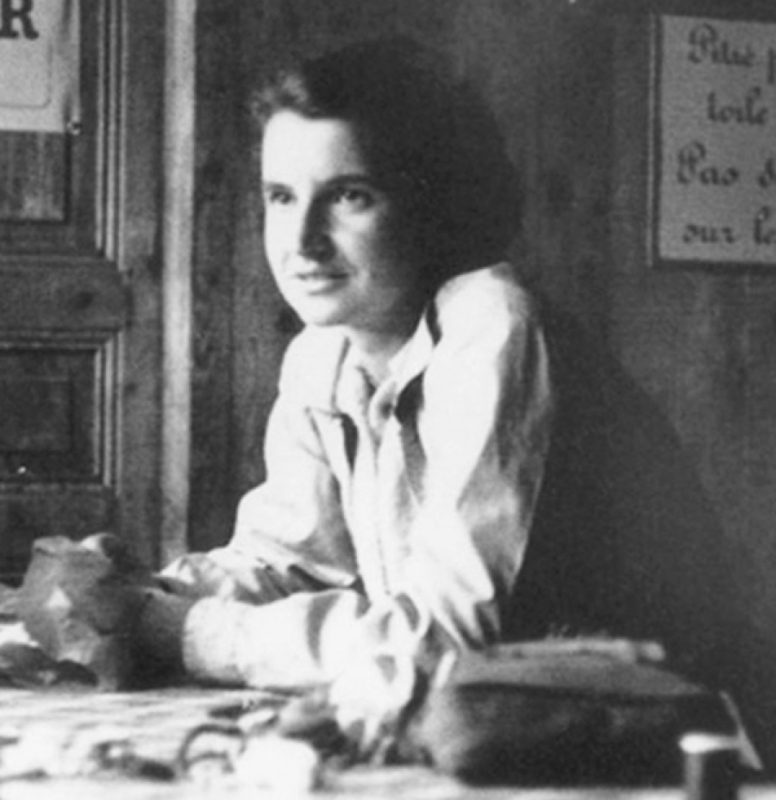

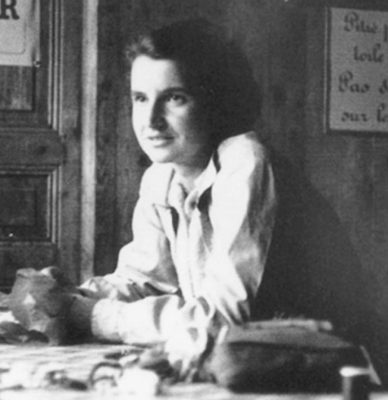

Rosalind Franklin

Has Rosalind Franklin’s status as a ‘wronged heroine’ overshadowed her scientific achievements?

Rosalind Franklin was a scientist and X-ray crystallographer who made significant discoveries in our understanding of the structure of DNA. When Cambridge University scientists Francis Crick and James Watson were awarded the prestigious Nobel Prize for medicine in 1962 they omitted to mention the significance of Rosalind’s discoveries in their acceptance speech.The failure of Francis and James to acknowledge the help they had from Rosalind’s research in their academic papers and lectures has served to portray Rosalind Franklin as a victim of the prejudices of a patriarchal scientific community, when perhaps we should be more focused on her amazing achievements in her short career.

DNA, the abbreviated name for deoxyribonucleic acid, is a complex molecule that exists in the cells of all living organisms. The term DNA has become part of our everyday language as a shorthand for the unique code that we all possess. All living things, be they plants or animals, have DNA within their cells, and nearly every cell in a multicellular organism possesses the full set of DNA required for that organism. Each human cell contains 46 chromosomes, 23 from each of their parents. Within each chromosome is a string of DNA that is individual to each person. DNA contains the chemical code that controls the way cells work and duplicate and operate like a set of instructions that tell a cell what to do and how to function. These codes are inherited from our parents and are unique to all living beings.

It was in the 1860s that a Swiss chemist, Friedrich Miescher isolated a previously unknown molecule from white blood cells, which he called ‘nuclein’, that is now known as nucleic acid. He wasn’t able to identify its function but he thought nucleic acid might have something to do with the process by which characteristics and qualities are passed from parents to their children before they are born. In 1943 Canadian Oswald Avery and fellow scientists isolated DNA and worked out that DNA was the material in cells that was inherited (passed from one generation to the next) from our parents, and that it contained a code for life. In March 1953, nearly a century after Friedrich Miescher’s discovery, two scientists at Cambridge University in England, Englishman Francis Crick and the American James Watson, assembled a spiral structure – a double helix – that demonstrated how DNA might look. On discovering the ‘coiled ladder’ structure of DNA and how it duplicated, James Watson proclaimed that they had ‘found the secret of life.’.

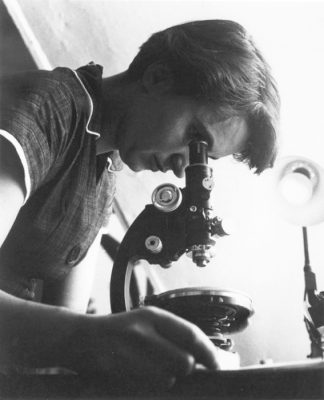

Subsequent analysis of the methods Francis and James had used to make their discovery found that they had used the findings of Rosalind Franklin and her student Raymond Gosling at King’s College London to help them work out the double helix arrangement. Rosalind and Raymond had been taking x-ray crystallography images of DNA to try to work out its structure. Rosalind deduced from the image the shape of the DNA in early 1953 and in March wrote a document proposing that a “helical structure [was] highly probable.” One of Rosalind’s colleagues at King’s that was also researching DNA was Maurice Wilkins. Maurice and Franklin had clashing personalities and did not get on well. Maurice was aware of the significance of Rosalind’s findings, and in his excitement in January 1953 at King’s College, he showed James Watson the image catalogued as Photograph 51 together with supporting data from Rosalind’s work, without her knowledge.

On April 25th, 1953, the scientific journal Nature published three articles on the structure of DNA. One was written by Francis Crick and James Watson; the other two articles were by Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins. The Cambridge scholars Francis and James were hailed for their discovery of the structure of DNA, but they had been helped enormously by the uncredited research findings of Rosalind and Maurice in London. Francis and James would achieve enormous credit, fame, and financial reward for their discovery. Rosalind and Maurice were destined to be overlooked for their contribution. James Watson was later to write a book called ‘The Double Helix’ that gives his account of the journey to discovering the structure of DNA. In it he is critical of Rosalind’s personality, appearance, and status in the research group at King’s College. He stated inaccurately that Rosalind “would not think of herself as Maurice’s assistant” and instead “claimed that she had been given DNA for her own problem.” He went on to say, “Clearly Rosy had to go or be put in her place.” While Rosalind’s sister Jenifer Glynn has subsequently described her as having a “rather sensitive and prickly nature,” contemporary accounts of Rosalind describe her differently. A colleague, Vittorio Luzattis, said that while Franklin “was not very easy to get along with… to some extent,” she nonetheless “was a very warm personality; she had good friends; many people liked her very much.” Like many women in the academic world in the 1950s, Rosalind was subject to sexist attitudes and prejudiced views. After much criticism, James wrote an epilogue to his book acknowledging that he had been unfair in his depiction of Rosalind. Even so, he still kept his original account of Rosalind in this book.

Rosalind Franklin has subsequently been described variously as ‘The Dark Lady’ and a ‘feminist icon,’ all due to the lack of recognition she received at the time for her work in the discovery of the structure of DNA. Rosalind’s sister Jenifer has been critical of some of the depictions of her sister as a ‘wronged heroine’ and described the many books as a ‘Rosalind industry.’ In an article in 2012 for the medical journal The Lancet, she wrote, “Her story has been adopted by feminists as a symbol of a woman struggling and unacknowledged in a man’s world. This would, I think, have embarrassed her almost as much as Watson’s account would have upset her. It suited the feminism of the 1960s and 1970s to portray her as a victim of male dominance, but she would have thought of herself simply as a scientist whose achievements should have been judged on their own terms, not as a “woman scientist” striking a blow for the rights of women.” Portraying her as a victim also puts focus on the perpetrators and a perceived injustice and takes away from her single-minded determination to use her knowledge of crystallography to solve scientific problems.

Prior to her work on DNA, Rosalind had already established herself as a scholarly X-ray crystallographer, notably with her work on coal. After leaving behind what had been an unhappy experience at King’s College, in 1953 she took up a position at Birkbeck College in London and later successfully applied for a grant to identify the structure of the polio virus. It was the largest grant that Birkbeck had ever received. Shortly after moving to Birkbeck, she was joined by another scientist, Aaron Klug. Rosalind collaborated with Aaron on working out the structure of viruses, which are much more complex than a single molecule like DNA. Their collaboration would not last long, as on April 16th, 1958, Rosalind succumbed to ovarian cancer. She was 37-years old. After her death it was found that Rosalind had made Aaron the principal beneficiary of her will. She had left him £3000 (the equivalent of £100,000 in 2024) and her Austin car. Aaron would later credit Rosalind, “not only with introducing him to viruses, but with showing him ‘that you have to tackle long and difficult problems rather than publishing clever papers.” In 1982, Aaron Klug won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for his development of crystallographic electron microscopy and his structural elucidation of biologically important nucleic acid-protein complexes.” In his Nobel Prize lecture, Aaron mentions Rosalind five times; he said, “It was Rosalind Franklin who set me the example of tackling large and difficult problems. Had her life not been cut tragically short, she might well have stood in this place on an earlier occasion.”

1. The Lancet article…